Closing Health Gaps in Rural Guatemala: Communication is Key

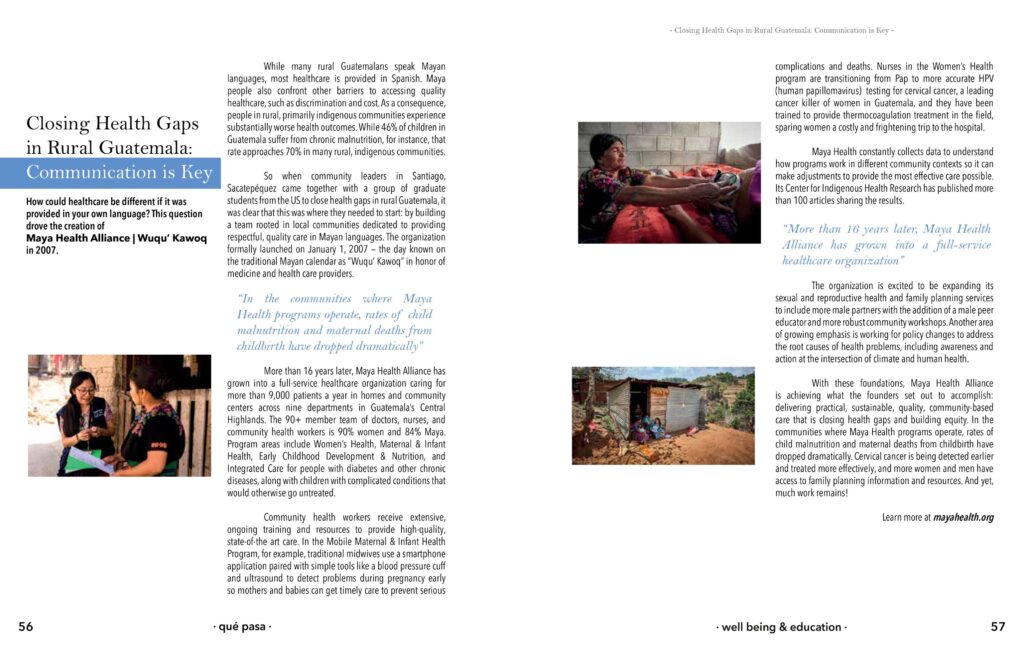

How could healthcare be different if it was provided in your own language? This question drove the creation of Maya Health Alliance | Wuqu’ Kawoq in 2007.

While many rural Guatemalans speak Mayan languages, most healthcare is provided in Spanish. Maya people also confront other barriers to accessing quality healthcare, such as discrimination and cost. As a consequence, people in rural, primarily indigenous communities experience substantially worse health outcomes. While 46% of children in Guatemala suffer from chronic malnutrition, for instance, that rate approaches 70% in many rural, indigenous communities.

So when community leaders in Santiago, Sacatepéquez came together with a group of graduate students from the US to close health gaps in rural Guatemala, it was clear that this was where they needed to start: by building a team rooted in local communities dedicated to providing respectful, quality care in Mayan languages. The organization formally launched on January 1, 2007 — the day known on the traditional Mayan calendar as “Wuqu’ Kawoq” in honor of medicine and health care providers.

More than 16 years later, Maya Health Alliance has grown into a full-service healthcare organization caring for more than 9,000 patients a year in homes and community centers across nine departments in Guatemala’s Central Highlands. The 90+ member team of doctors, nurses, and community health workers is 90% women and 84% Maya. Program areas include Women’s Health, Maternal & Infant Health, Early Childhood Development & Nutrition, and Integrated Care for people with diabetes and other chronic diseases, along with children with complicated conditions that would otherwise go untreated.

Community health workers receive extensive, ongoing training and resources to provide high-quality, state-of-the art care. In the Mobile Maternal & Infant Health Program, for example, traditional midwives use a smartphone application paired with simple tools like a blood pressure cuff and ultrasound to detect problems during pregnancy early so mothers and babies can get timely care to prevent serious complications and deaths. Nurses in the Women’s Health program are transitioning from Pap to more accurate HPV (human papillomavirus) testing for cervical cancer, a leading cancer killer of women in Guatemala, and they have been trained to provide thermocoagulation treatment in the field, sparing women a costly and frightening trip to the hospital.

Maya Health constantly collects data to understand how programs work in different community contexts so it can make adjustments to provide the most effective care possible. Its Center for Indigenous Health Research has published more than 100 articles sharing the results.

The organization is excited to be expanding its sexual and reproductive health and family planning services to include more male partners with the addition of a male peer educator and more robust community workshops. Another area of growing emphasis is working for policy changes to address the root causes of health problems, including awareness and action at the intersection of climate and human health.

From Qué Pasa Printed Edition 139. January 2023

With these foundations, Maya Health Alliance is achieving what the founders set out to accomplish: delivering practical, sustainable, quality, community-based care that is closing health gaps and building equity. In the communities where Maya Health programs operate, rates of child malnutrition and maternal deaths from childbirth have dropped dramatically. Cervical cancer is being detected earlier and treated more effectively, and more women and men have access to family planning information and resources. And yet, much work remains!

Qué Pasa sat down with two of the many contributors to this book: Dr. Peter Rohloff, M.D., Ph.D., and co-founder of the non-governmental healthcare organization Maya Health Alliance|Wuqu’ Kawoq, and Anita Chary, an M.D. and Ph.D. candidate at Washington University in St. Louis.

This book, Privatization and the New Medical Pluralism: Shifting Healthcare Landscapes in Maya Guatemala, takes patient stories and leading-edge research and synthesizes them to create a critical look at the challenges, opportunities, and changes that impact healthcare for the Maya population in Guatemala.

What led you to write this book?

PR: We felt there needed to be an up-to-date account of how the Maya attain healthcare. Since the Peace Accords [in 1996], there have been so many changes – including privatization and outsourcing. Most accounts of healthcare haven’t adequately dealt with this.

AC: I remember a patient that Wuqu’ Kawoq had in the summer of 2010, Gloria, whose daughter had been sick with a cough. We were really struck by the number of healers and doctors she had gone to, seeking treatment for her daughter. On top of going to the herbalist at the local market, a pharmacy, and one of the community elders – which were the expected sources of care for someone in a rural community – Gloria had actually gone to a private clinic a few towns away and to an NGO mission clinic sponsored by Americans.

She had collected an assortment of remedies at quite a high price, but was too afraid to use any of them, because she was so accustomed to getting poor medical advice that she didn’t know who to trust. In a sense, this family had very little access to care, but in another sense, there were actually a number of options available to them – the options were just of varying quality and costs, none of them were connected, and the whole experience was extremely fragmented.

As a team, we borrowed from the language of anthropology to talk about how patients were engaging in “medical pluralism” – that is, accessing diverse healing systems, both traditional and biomedical, and turning to multiple sectors for their care: the public governmental health system, private for-profit clinics, and the increasing number of NGOs providing healthcare throughout the country.

The idea for putting together this book emerged because we really wanted to understand exactly how our patients experience, on one hand, such limited access to healthcare, and on the other, a fragmented and unpredictable variety of services, as well as the challenges such a system poses to us as providers in terms of knowing how to help patients navigate through all of the options, and how to be there for them, accompanying them through it all.

What’s the take-home message of this book?

PR: The Maya are resourceful, and they attain healthcare in incredibly creative ways. Increasingly, they do this by engaging with private or nonprofit healthcare providers – rather than government services – and they usually pay for these services. This is the new context for designing healthcare solutions in Guatemala.

AC: We are hoping that this book provides people with a sense of some of the challenges and opportunities that rural indigenous Guatemalans face on a daily basis as they try to get healthcare. It’s the only book that really describes in detail Guatemala’s health system, both the history of it and what it looks like today.

What is your hope now that the book has been released?

PR: We want to spark new conversations about medical anthropology and healthcare delivery in Guatemala, conversations that take seriously how rapidly healthcare is changing and evolving, and how important it is for our solutions to be up-to-date.

AC: In this book, we showcase the difficulty of accessing healthcare in Guatemala. But we can learn from these experiences, and there are success stories. There are windows of opportunity, places where we can intervene. Once we know how a health system works – in nitty-gritty detail – we can anticipate the challenges and work with all of the potential avenues, all of the loopholes, to provide our patients with the high-quality care they deserve.

This groundbreaking book, which has now been released, is an important addition to literature on global health, marginalized communities, and in particular the situation here in Guatemala. It’s definitely worth the read!

Web: www.wuqukawoq.org

Maya Health Alliance